THE first report in the Stroud News of Friday August 7, 1914, three days after war had been declared, was headed “Interesting Local Wedding” and told of the marriage of Miss Nora Kathleen Lane of The Lawn, Cainscross, to Mr Henry Miller of Las Palmas and London.

“The future home of Mr and Mrs Miller will be at Las Palmas,” the account concluded and that must surely have been a “first” in the paper’s long history.

There would be many more “firsts” over the coming years, tales of local men performing heroics and as often as not laying down their lives in far-away places with strange-sounding but now chillingly familiar names – Passchendaele, Ploegstraat, Ypres, Gallipoli.

And that issue of August 7, compiled largely in the last days of peacetime would be the last for years to be dominated by fetes, outings, church and political news and the other nuts and bolts of small-town country life.

Apprehension but quiet optimism were to the fore in the first couple of issues of the month. The August 7, leader column, headed “Britain at War”, was spot-on in declaring that the country was now “face-to-face with the greatest trial in its history” but naive, as the bulk of the country was, when it called on God to “grant that, before many months have passed, we shall witness the downfall and the final end of an armed and provocative organisation whose schemes have long been a menace to the peace of Europe and the world”.

The paper was quickly on to aspects of the war it could cover best, its immediate effects on local life and business. On August 7 The News reported the banks, closed for fear of panic withdrawals would reopen that day.

Every Territorial and Army reservist had already been called up – one of the latter, Fred Shipton of Nailsworth, to the great disgust of his boss, county councillor Matthew Grist JP, who thought he had sloped off without giving a week’s notice and took him to Nailsworth Police Court to claim his 18 shillings wages back. His friends on the bench wisely persuaded him to let it drop.

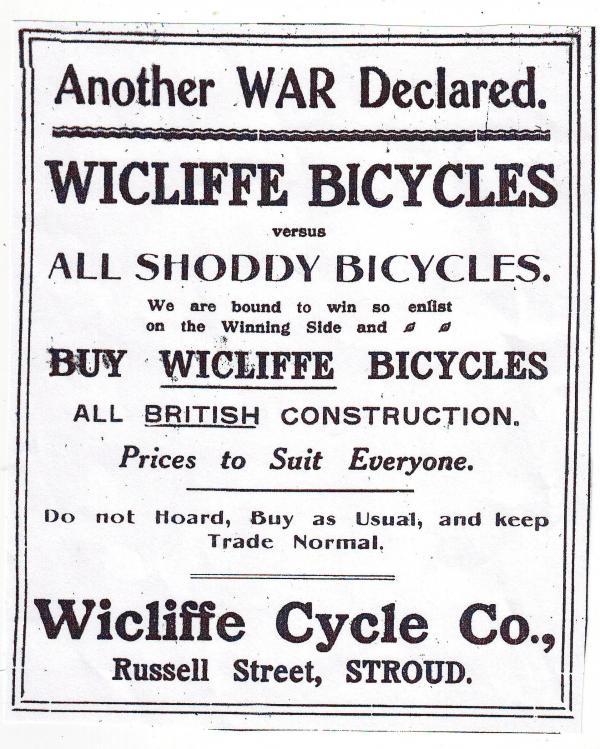

The hoarders were instantly out in force: “In quite a number of instances, cautious housekeepers secured considerable stocks and consequently there was very quickly a shortage. This policy, we believe, is a mistaken one, for with our Navy predominant, we should command the trade routes to America and Asia and Africa, and food supplies should come in freely.”

The grocers of Stroud – Fawkes Bros, Mills Bros, Hawkins, Lipton’s, the Co-Op and the rest – speedily introduced ad hoc rationing, restricting customers to no more than their usual order. Nevertheless, “prices have gone up with startling rapidity”, and “motorists coming through Stroud referred to the enormous prices asked in various places for petrol... on Tuesday it was practically unobtainable.”.

Response to the news tended to be sombre and ceremonial, rather than spontaneous: “At Nailsworth on Tuesday night there were exciting proceedings. Until quite a late hour large crowds assembled round the flagstaff near the church, and the National Anthem and several patriotic songs were lustily sung beneath the waving Union Jack...”

Similar scenes were reported fromup on the Common, though a couple of weeks later: “The little excitement which prevailed last week in Minchinhampton has now subsided and affairs are confined to their ordinary everyday course.”

It took more than a world war to disturb the repose of Minch, though the correspondent was forced to admit that: “The only demonstration of enthusiasm has been when an old soldier has been called upon to leave for the front and the farewell on such an occasion has been hearty.”

When the local company of the Gloucester and Worcester Brigade “entrained” to Swindon: “There were many spectators and these were interested in the movements of the soldiers... loading wagons and getting horses on board. At last, however, they marched smartly to the Great Western station from where the special train departed... and as they moved off they were heartily cheered by their relations and friends.”

There was less cheer for drinking men with the requisitioning of brewery wagons – three from Stroud Brewery, one from the Brimscombe Brewery, one from Godsell’s of Salmon Springs while the instant commandeering of horses for the army raised fears of more widespread transport problems.

News from Europe came from an agency that specialised in glad tidings: “A sergeant from Liege states that the German troops are spiritless. He says that a high officer on the German staff, in despair at not capturing the Forts, shot himself. Subsequently eight soldiers drowned themselves in the river Meuse...”

In real life, Liege had fallen to the Germans almost a week previously.

Even before the end of the month, however, the Stroud News began to see the light.

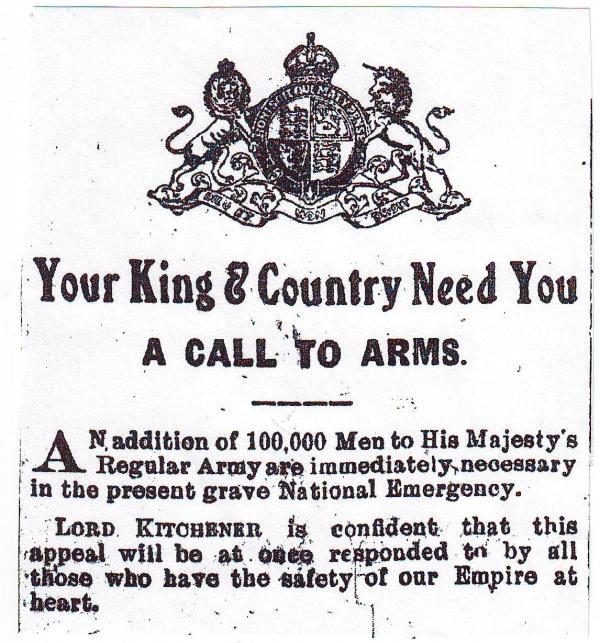

On August 23, the British forces’ “tactical” retreat from the Battle of Mons was the public’s first great reality check, while closer to home, the newspaper was fretting that local men were not joining up with the enthusiasm expected of them.

There had been various local rallies addressed by Major Martin Archer-Shee, a London MP from a prominent Nailsworth family who was best-known for helping in the recent defence of his young half-brother George, a naval cadet who was acquitted of stealing a five-shilling postal order only after the case had gone all the way to the High Court; the tortuous trial later inspired Terence Rattigan’s play The Winslow Boy.

It seems the meetings were more popular with elderly non-combatants than potential fighters: “The various addresses that have been given in the Stroud district by Major Archer-Shee with the object of raising recruits for Lord Kitchener’s Second Army have attracted large audiences, and in one or two parishes the results... have undoubtedly been gratifying to him, but in others we do not think the response has proved worthy of the district.

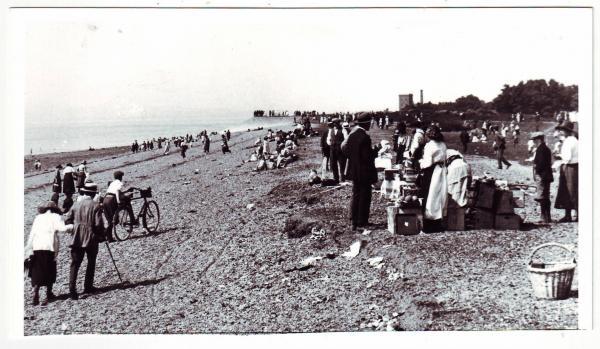

“At the Stroud meeting held last week, for instance, there appears to have been a great deal of vocal enthusiasm but rather negligible results from the recruiting point of view, and all the vociferous applause of which our lungs are capable has not the material value of a single recruit.”The paper also disapproved of young men joining their families at the seaside on August Bank Holiday, the day before war was declared.

All this moral turpitude, in the newspaper’s view, was compounded by a public lack of awareness “of the immensity of the task we have undertaken; and we fear, before this ill-based optimism is removed, many rude shocks to the national complacency will have been administered by a ferocious and determined enemy.”

That opinion column was written just three weeks after the paper had speculated that the task in hand might take some months. And how long would it be before disturbingly vague reports of British losses would be transformed into the stark news of the death of local lads? The answer to that question, inevitably, was not very long at all.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here