Stroud’s Museum in the Park has an archive collection which includes a multitude of sources relating to the town during general election campaigns. Hayden Searle, 18, from Chalford Hill, who is hoping to study history at university, analysed sources in the collection relating to Liberal and Conservative electoral campaigning in Stroud for the 1868 general election. He has written this article for the SNJ.

---------------------------------

FROM the general election last year to the EU referendum in June, Stroud has recently seen its fair share of political decisions.

There have been various forms of election materials telling us how to vote, and Stroud has not been immune from so-called “negative campaigning”.

What many may not realise, however, is that such persuasive techniques during elections are far from a recent addition to Stroud’s history; these practises were also a vital part of elections well over one hundred years ago.

The Liberals and the Conservatives were the main political parties in the late 19th century.

In many ways, their political battle in Stroud in 1868 was a microcosm of British politics, mirroring the Disraeli-Gladstone rivalry.

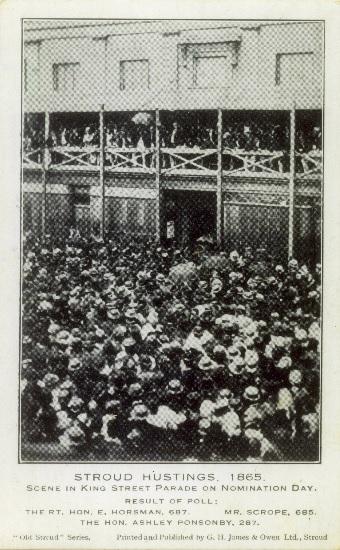

The museum’s collection of sources on the 1868 general election includes propaganda posters, newspaper articles and manifestos.

When analysing these, it is noticeable that a focus of both Liberal and Conservative election propaganda in Stroud was on obtaining the votes of the newly-enfranchised working class.

Following Disraeli’s 1867 Reform Act, the 1868 election was the first time that parties in Stroud needed to attract these working-class voters.

Although aristocrats and industrialists, with lifestyles very different to ordinary people, constituted the Conservative and Liberal parties in similar proportions, Liberal propaganda in Stroud continued to play on the supposed lack of Conservative empathy with the “common man” by claiming that the Conservatives did not understand the problems of ordinary people.

Propaganda posters claimed that Dorington, the Conservative defeated by his Liberal opponent in Stroud in 1868, greatly underestimated the hardship faced by many ordinary people in Stroud.

Liberals attacked the Conservatives explicitly for supposedly trying to “keep a cheap loaf from the working man” with their policies.

As well as Liberal appeals to working class voters, the Conservatives tried to gain votes by attempting to rid themselves of the image of them as enemies of the poor.

Articles assuring the working class that the Conservatives in Stroud contained “a large number of your truest friends” and commanding the working class to vote for Dorington, promising to “remove the oppressive burdens upon the poor,” demonstrate this.

The large proportion of propaganda appealing to the working class demonstrates the change that occurred in Stroud’s election campaigns: although Liberals and Conservatives in Stroud had historically only needed to win the votes of the financially independent, the extension of the franchise to many members of the working class meant that election strategies had to change.

However, the sources also support a more nuanced interpretation – that the Liberals and Conservatives tried to appeal to the working class while maintaining as many policies popular among their wealthier traditional support bases as possible.

For example, despite Dorington’s propaganda largely trying to persuade the working class to vote for him, policies relating to elevating the conditions of working people were marginalised when he communicated his policies to the Stroud electorate.

Outlining his manifesto in the Stroud News in August 1868, Dorington mainly mentioned policies related to the political interests of the educated middle and upper classes, such as Ireland and universities.

Most significantly, much of Dorington’s policy justification rested on reducing the supposed affliction of taxes or “rates” – a major issue for the wealthy but less so for working people.

The idea that electioneering in Stroud was significantly modified by the extension of the franchise may, then, be misleading.

While different propaganda was certainly used, the parties by no means ignored their traditional support bases.

The new electorate in Stroud was not synonymous with a new set of policies; continuity rather than change characterised Stroud politically at this time.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here