Anthony Burton adores all things steam. So much so that he’s more inclined to take a boiler - not bathing - suit when he goes on holiday, he tells me in his study. The reason for my visit: the Stroud-based author has spent the last few months buried away in archives to dig up the story of how Brits gave railways to the world. The result is his new book, 'Railway Empire'.

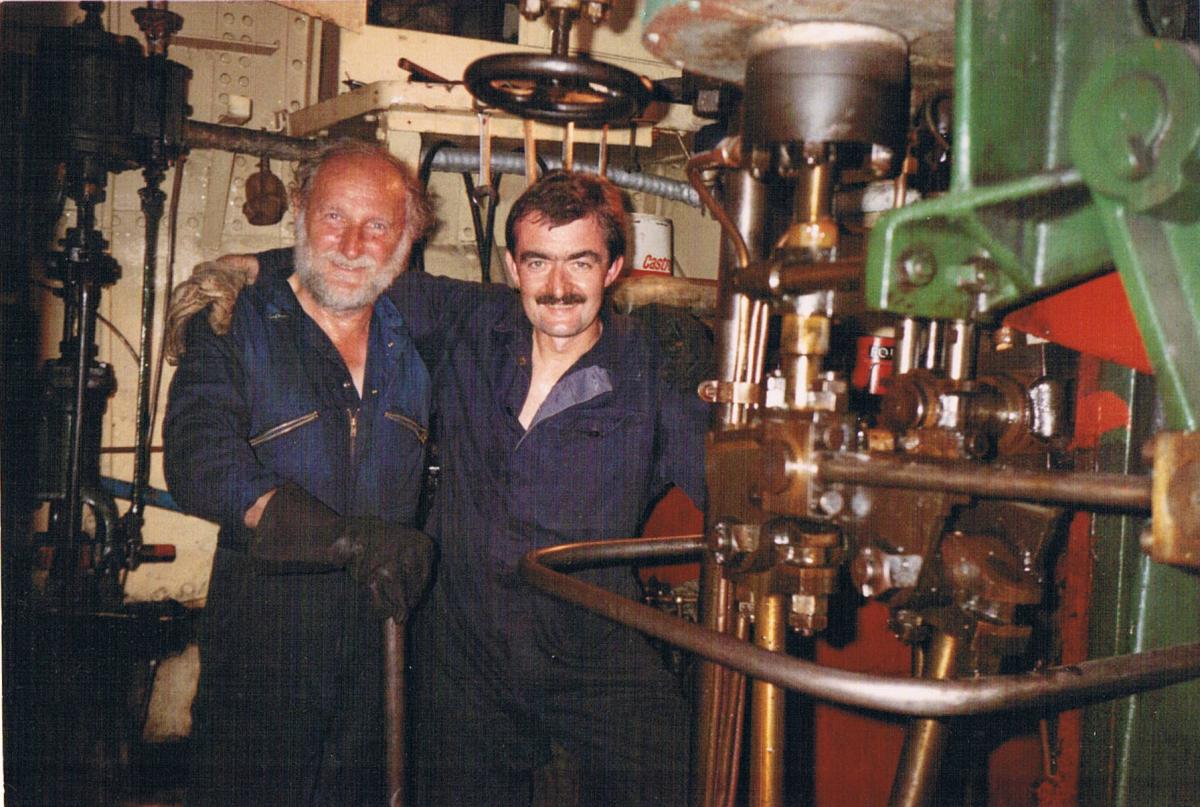

The title of Anthony’s previous work, 'A Steam Engine Pilgrimage', betrays his quasi-religious love of locomotion. Released last year, the book tells the tale of a man prepared to shovel coal from one end of the British isles to the other, chugging for chugging’s own sake.

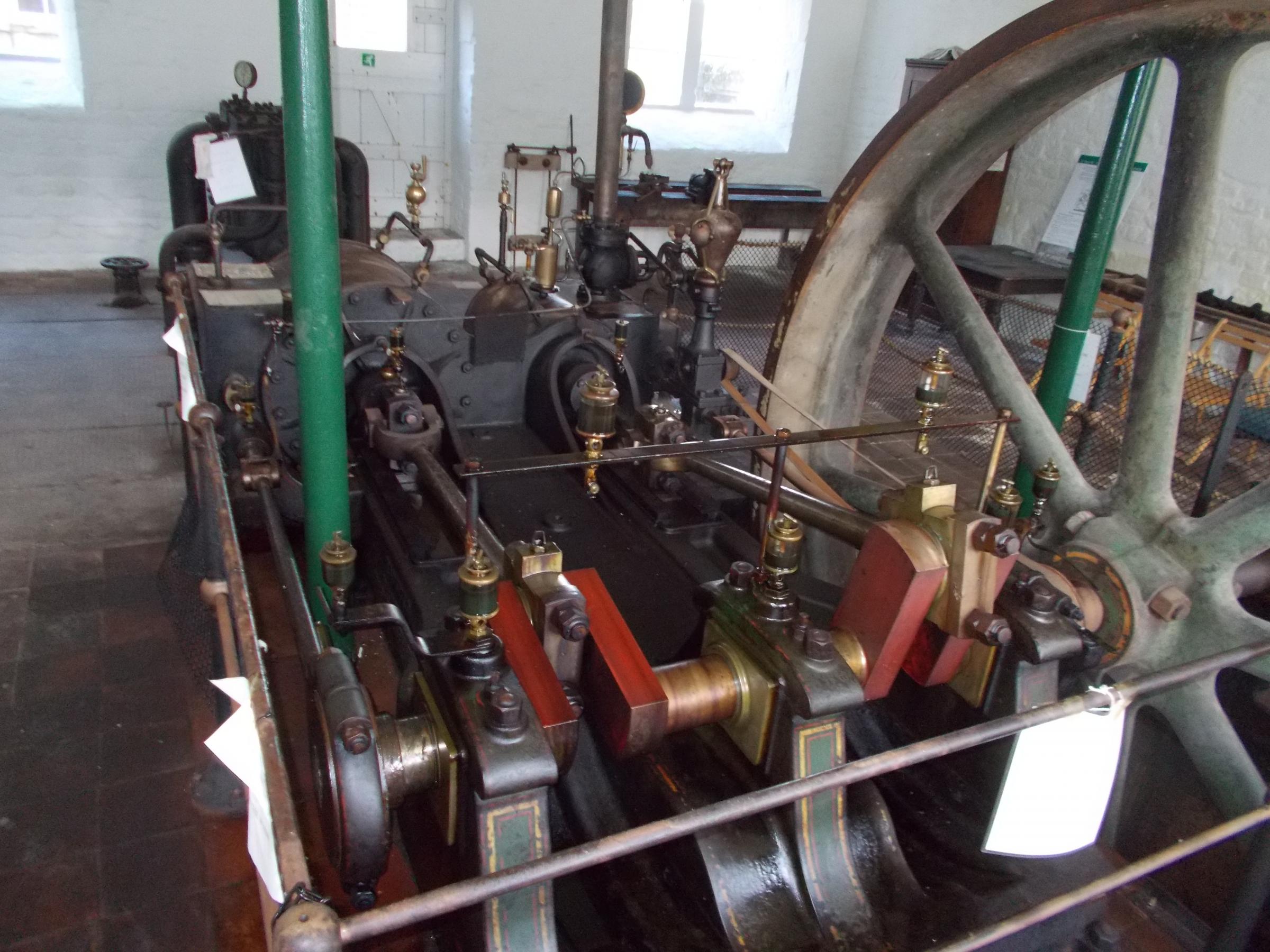

One of Anthony’s stops was St Mary’s Mill in Chalford, home to the powerful Tangye Steam engine, and a shrine to steam for local enthusiasts. Indeed, Stroud clearly suits Anthony’s passion - “when we moved, we wanted somewhere with an industrial heritage” - and he takes an active role in preserving the town’s past, having helped found the Stroud Textile Trust. Anthony is also an old hand at spotting the vintage steamers that regularly shoot through Stroud station.

The steam engine at St Mary's Mill, Chalford

Even his own four walls are imbued with local history, his house having previously been the site of a synagogue for Jewish workers who came to Stroud bringing garment expertise - he suggests one too many bacon breakfasts may have cost him the favour of any phantom rabbis he may still share the building with.

But for 'Railway Empire', Anthony casts his eye further afield than the Five Valleys; no less than the whole globe in fact. The book is an ambitious piece of political, economic and technical history that charts how British engineers and navvies - manual labourers contracted to build railways - flocked to the empire and beyond, bringing tracks, trains and, moreover, know-how in their wake.

Anthony's new book, 'Railway Empire'

He writes of a Britain that was “king of the castle” during the 19th century, its industrial expertise in demand worldwide. Any country attempting to kick off its railways system “needed Brits over there”, argues Anthony.

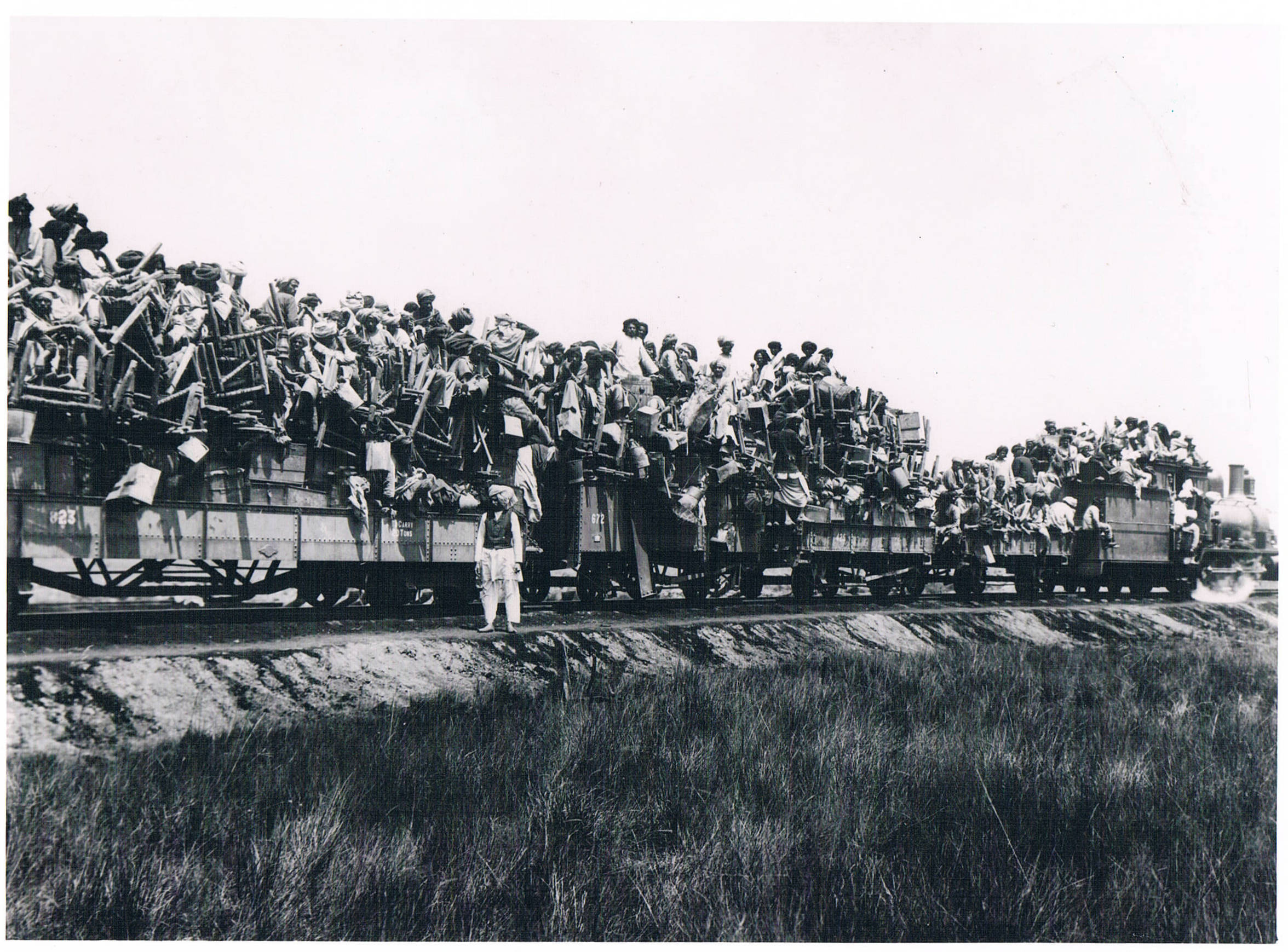

Some of the characters who star in this story are renowned industrialists like Robert Stephenson, who, for instance, replicated the design of his bridge over the Menai Straits in Wales for Canadians looking for a way to cross the St Lawrence River. Others are more keenly forgotten, like the 10,000 Indian workers stricken down by cholera as they built their country’s railways under British rule

Robert Stephenson's bridge over the St Lawrence river

Presenting transport documentaries for the BBC has allowed Anthony to see Britain’s lasting impact first hand. Take India, whose railway offices, he says, are a “British bureaucracy still at work” - and a tightly guarded one at that. In Mumbai, Anthony and his film crew, hunkered down in an old cinema to get a few shots of an office across the road, found themselves interrupted by trampling boots and soon under arrest. They were eventually let go - but his cameraman, having been mobbed by children seemingly innocently interested at the sight of a few Brits in custody, couldn’t find his wallet.

Indian workers on the Uganda Railway

When I ask Anthony how Britain’s rail empire stands today, his tone turns notably sombre - not good, in short. Britain is no longer a major rail exporter, and most innovation is taking place elsewhere, such as Japan. Spotting an old British train abandoned atop a scrap heap while on a trip in South America had obvious symbolism for Anthony. More locally, he particularly laments the closing of Swindon Works - not least because it coincided with the 150th anniversary of Great Western Railway.

The (stuffed) man-eating lions of Tsavo

So it is perhaps fitting that, before I leave, Anthony tells me the story of the man-eating lions of Tsavo, which repeatedly dragged off construction workers as they attempted to build the Kenya-Uganda railway. British ingenuity (and the bravery of one poor soul who waited in a cage as bait) eventually led to their capture. Today, these once fierce and feared lions - the traditional symbols of Britannia and in turn her industrial achievements - sit stuffed in a museum.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here